This week I wanted to discuss a topic that can possibly reduce a gymnast’s risk of lower back pain, as well as help improve their skill performance. Many people have asked me about how to address bridges that lack mobility and how to deal with lower back pain related to back bending type skills. I would think that most coaches agree with me in saying that a proper bridge is one of the most fundamentally crucial positions an athlete needs to be successful in gymnastics. I think many coaches would also agree that helping an athlete who has chronic difficulty acquiring a proper bridge is quite frustrating. Many versions of a bridge/arch are needed for hundreds of skills in both men’s and women’s gymnastics. Some skills with different bridge/arch movement requirements include,

- Holding a static arch or bridge (poses, flexibility drills, shaping drills, strength exercises). I thought this picture was awesome by the way.

- Moving through a bridge slowly with smooth and balanced motor control (back bend, back/front walk over progression, drills)

- Moving fast through a bridge with explosive power, which is most important for higher level skill development (front/back handsprings, giant and bar taps, beam tumbling , tkachevs, yurchenkos, and the list goes on)

If you were to ask a handful of coaches what area of the body contributes the most to a great bridge shape, many would say lower back flexibility. The lower back or lumbar spine actually is an area that is primarily build for stability, and really shouldn’t be the primary method of extension for a gymnasts bridging skills. Gymnasts typically acquire lower back hyper extension flexibility as they attempt to learn skills that are of higher level, often times through a compensatory method for the missing range of motion or mobility else where. The distribution of forces for the extending position should ideally be across multiple joints and structures evenly, so that one area does not get a huge increase in stress (often times called a focal loading point). There are two other structures that play a huge role and are typically not addressed. Coaches must be sure to investigate the influence that joints above and below the lower back have on a bridge. Along with lower back mobility, the gymnast’s hip flexor and shoulder mobility must be sufficient to reach a full bridge position. The athlete must be able to open their hips up fully (hip extension) and open their shoulders behind their head (shoulder flexion/hyper flexion).

After seeing a bridge that needs some construction (I know, bad joke), I try to tease out what the main reason behind the restriction is. Using some techniques I will describe below, I try to find out whether the shoulders, lower back, or hips are the reason behind the poor bridge shape. By knowing which is to blame, you can then tackle the issue more specifically. When initially looking at the athlete, the scenario that I most typically see is:

- The athlete has a lack of TRUE 1 joint hip flexor mobility, meaning that they are unable to open their hips fully ( into hip extension). The athlete usually has a habit of compensating with their lower back. This hip flexor restriction/lower back compensation coupling creates the slight “butt out” position that is often seen in a bridge.

- The athlete has a lack of shoulder flexibility into hyperflexion, secondary to tight and overdeveloped latissimus dorsi muscles, pectoralis muscles a lack of thoracic extension (bending from your middle/upper spine), tight shoulder joints, improperly positioned shoulder blades, overhead stability issues, and chronic “rounded shoulder” posturing due to upper trunk muscular imbalances. This creates a scenario where the gymnast is unable to fully open their shoulders behind their ears. This causes the athlete to again compensate using their lower/middle back to make up the lack of motion. This shoulder restriction/lower to middle back compensation coupling causes the closed shoulder position that forces athletes to depend on strength alone to hold themselves up.

- Lower back flexibility is usually excessive (hyper mobile) as a result of the first two restrictions. Over time habit develops, and the athlete tends to bend/hinge from one or two lower back segments more than all of the others. Below is an example of what this would look like. Keep that last point on the front of your mind as you read on.

Ideally, the gymnast should demonstrate an equal distribution of the mobility demand through the shoulders, lower back, and hips during a bridge. This reduces the workload of one structure and helps to disperse the force created by a bridge. Note below the equal distribution of forces through the shoulders, lower back, and hips. The athlete does not have to hinge from the back nearly as much to reach the position as in the pictures above. I’ve been trying to wrap my head around a way to create a term for this concept, and so far the only one fitting is “bridge mobility coupling”. There may very well be another term for it I haven’t stumbled upon yet. The athlete must possess and utilize paired (“coupling”) mobility for shoulder hyperflexion , spinal extension, and hip extension to optimize their bridge and reduce strain. Each of the three main components have their own set of factors that could limit the overall mobility, and there are certainly other factors that go into it. I’m kind of creating this concept and term based on what I see and find in gymnasts, but hey it’s a start.

Statically as the pictures show, it may be hard to imagine if you have gymnasts who show these characteristics. However, I bet if you think about the multiple skills with bridges/arches that your athletes struggle with you may be able to recognize some familiar scenarios. Common examples include front handsprings that lack shoulder or hip flexibility and fall backwards, beam back handsprings that undercut due to a lack of shoulder or hip flexibility, and difficulty with long hang swing skills on bars from the lack of an arch tap at the bottom of the swing.

So Why Does It Matter?

As I mentioned in the discussion about flat feet, you may be thinking that this is nothing more than an athlete having a rough time with a bridge. However, I again hope to steer you in another direction by reading. Having restrictions in the hips and shoulders may cause the back to take all of the workload during hyperextending/bridging, and a few vertebral joint levels typically get overworked. This is huge to realize and understand because it can possibly be how an athlete gets progressive back pain due to gymnastics, and possibly some more serious lower spine issues.

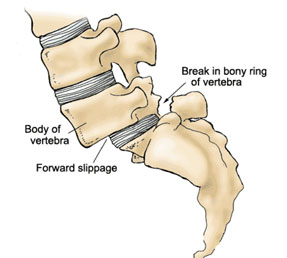

Repetitive overuse of the lower back at one or two segments may possibly lead to joint inflammation, muscular strains, tissue irritation, and ligamentous sprains. More dangerously, spine pathologies can develop where a vertebrae slips forward in spine (spondylolisthesis) causing pain and biomechanical mal-alignments. In more severe cases a piece of the vertebral bone gets fractured (spondylolysis). The most common site for many of these problems is the L4/L5 junction (very lower spine above buttocks), and many times this is the area gymnasts complain of pain. If the hip flexors and shoulders aren’t properly mobile and do not share the tension load, the lower spine will have to do all of the work and may possibly get injured.

Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

http://www.pt-works.com/images/spondylolisthesis.jpg

Lumbar Spondylolysis

http://www.massgeneral.org/ortho/assets/images/pediatrics/spondylolysis-spine-drawing-l5s1.jpg

When an injury occurs from this scenario, many athletes become caught up in common dilemma of whether they should listen to their body, coach, parent, or doctor. The doctor says they have to stop gymnastics , a coach wants the athlete to keep practicing as much as they can, parents get overwhelmed, the athlete’s lower back is screaming during practice, and the gymnast feels hopeless. This is why I think this topic is important, to possibly prevent a few of these scenarios from happening.

Now this being said, the PT side of me certainly knows the amount of spinal extension/backwards bending gymnastics requires is inherently dangerous. There are definitely times when it is simply the sport that causes problems, and it is an unfortunate conversation that sometimes takes place about an athletes safety. Along with this, I am not saying that this is the exact reason many athletes may develop pain. Sometimes lower back pain can be a very complex beast to tackle. There are many other causative influences that can play a role such as true core strength deficits, poor neuromuscular control during skills, repetitive high impact forces, postural habits, and the list goes on. This is simply a common scenario I have seen, and addressing the right anatomical structure has helped some athletes I have worked with. I believe by taking the time to look an athlete’s hip flexors and shoulders you can both reduce the possibility of pain and increase the athletes performance/skill development/scores. So with this being said, here are some techniques to help.

Hip Flexor Mobility:

A few weeks ago I wrote my first blog on how to go about tackling this issue. I went through how to look for specific hip flexor restrictions, and offered some advice on how to increase hip mobility. You can read that post by clicking here. As I noted above often times athletes lack true 1 joint hip flexor mobility and compensate with their lower back. There are a lot of tips and techniques to increase a athletes 1 joint hip flexor mobility within the post with pictures to reference.

Shoulder Mobility:

This content relative to shoulder flexibility is new. There are a few muscles within the upper back and thorax (chest) that can play a role in how far your athlete can reach over head. If these structures are over developed and not adequately flexible, the athlete may have difficulty moving into shoulder flexion (arms overhead behind the ears). Although many can influence this, two major ones I will address are the latissimus dorsi, and the pectoralis muscles.

The latissimus dorsi muscle functions as a shoulder extensor, internal rotator, and adductor (arm pulled back with the palm facing away and close to your spine). This muscle is used in all three ways when you reach into your back pocket. When this muscle is overworked and does not get mobility restored, it can be tight and prevent an athlete from reaching up over head fully.

Latissimus Dorsi Muscle – http://www.exrx.net/Muscles/LatissimusDorsi.html

In gymnastics this muscle is important and used all the time. Examples include:

- Any movement that closes the shoulder angle for forward motion, closing the shoulders for back handsprings, snapping into front tumbling, giants, snapping down motion, and many more

- Pulling down on the bar for kips, front giants, uprises, etc.

- Strength like pull ups, pull overs, chin ups, etc

- Almost every men’s ring move like crosses, planches, swinging. Also stabilization in upright support for mens events like parellel bars and pommel horse

Due to the latissimus dorsi being crucial for gymnastics, athletes are usually very overdeveloped in this area. Along with this, they aren’t generally stretched or mobilized as frequently as the lower body and trunk. Pair overuse with under stretching and the athlete develops the imbalance of not being able to bring the arm overhead. Here is a way to test if the latissmus dorsi is tight, then techniques to reduce tension and increase mobility.

Latissmus Dorsi Test/Thoracic Extension Test

- Have the athlete lay on a spotting block with their shoulders close to the top of the mat

- While keeping the lower back completely pressed against the block, have the athlete raise both arms over head . If an athlete has restrictions, they may arch their lower back off the block showing what might look like normal overhead mobility

- A restriction or tightness of the lats, or possibly a stiff middle back/thoracic spine, might be the case if the athlete is unable to bring their arms fully overhead and feels tightness in the side of their chest/back area.

Myofascial Release for Latissimus Dorsi: These were from an earlier post, but I will include the pictures again. Athletes can use foam rollers, golf balls, lacrosse ball, or tennis balls to release tension points through the lats. This will help reduce tightness in the lats and in turn, possibly increase their ability to reach overhead for a bridge.

Latissimus Dorsi/Overhead Shoulder Flexion Stretching: One good way to stretch the lats, which many people already know of, is to do an elevated “cat” like stretch. Have the athlete move to a floor beam or bench, and grab both hands. While keeping the back flat, have the athlete pull back on the beam with straight arms. If sitting on back aggravates the athletes knees, they can push up off their heels or use a higher beam. A bilateral approach (both arms) will allow a good stretch, and the athlete can then lean their body to one side for a unilateral stretch (one side) at different angles.

Thoracic Spine Extension:

- Another great way gymnasts can gain some overhead motion is to increase the amount of extension (bending backwards) in their middle spine or thoracic spine. Hypermobility and hinging from a few segments of the lumbar spine, along with postural habits and poor movement patterns can all cause the thoracic spine to get locked up. This then influences the shoulder blade positioning, which then links to faulty shoulder joint movement one of which may be limited overhead reaching abilities. To improve this motion have an athlete lay over a foam roller with it about shoulder blade height, and gently extend back, only moving from their middle spine. The athlete can also use a light weight to help add some pressure, be sure to go lightly and keep good form while doing this (the gymnast shouldn’t feel their lower back or head moving too much).

Band Assisted Overhead Shoulder Mobilization Stretch: A gymnast can also integrate both the mobility work from the foam roller , their flexibility drills, and the myofascial release into a functional band assisted stretch that helps with overhead motion. The band helps to both add some pressure into the stretch (without a partner) in their own pressure tolerance, and also assist in the shoulder joint gliding properly if the joint capsule is stiff. Using a green band the athlete will anchor it to a low bar spreader base (with the bar lowered all the way down), kneel down, loop their hand arm through and grab onto the low bar. Make sure the band is just above the shoulder joint. The athlete will then move their body forward while still gripping the bar, helping to move the shoulder overhead. Be sure to instruct the gymnast to go gently, and only perform this stretch on people with restricted shoulder mobility. Wrongly doing this on some with excessive mobility (which many gymnasts have) can cause damage or injury due to laxity. Here’s a picture for an idea of what it looks like.

Pectoralis Major: The other muscle that is overused and under stretched is the pectoralis muscles. This muscle is responsible for horizontally adducting the arm, the motion of putting your arms together in front. Some of the lower fibers move in a diagonal fashion towards the bottom of the sternum, and when they are tight may play a role in restricting overhead shoulder flexion motion.

Pectoralis Major Muscle – http://ittcs.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/img_0363.jpg

Examples of the use of this muscle in gymnastics include

- Any major “pushing” motion for strength, blocking for vault motions, and tumbling

- Bringing the arms close to the body for turning, wrapping in for twisting, and shaping drills

- Maintaining pressure and control over small area for beam

- Multiple men’s gymnastics events like the majority of all ring motions to generate power, strength holds, large contributor to parallel bar and pommel horse stability

The pectoralis muscles also become tight because a gymnast typically always uses them with skills and conditioning, but does not appropriately strengthen their middle back to counterbalance the postural habit. This is why many athletes have the “rounded shoulders” look to them. Tightness within the pectoralis muscles can also possibly contribute to a lack of mobility over head, poor biomechanics of the shoulder joint, and possibly some overuse injuries. Here are some techniques to increase mobility of the pectoralis muscle, and strengthen the middle back musculature to combat a biomechanical shoulder imbalance (shoulder joint not being ideally positioned).

Myofascial Release for Pectoralis: This also was from a previous post, but here it is again. Using a lacrosse ball or golf ball on the edge of a floor will help release tension points within the pectoralis muscle.

Pectoralis Muscle Stretching: Have the athlete lay on their stomach with their arms up at shoulder height, and elbow bent to 90 degrees. Keeping their shoulder flat on the floor, have the athlete rotate away from the arm being stretched until it is felt in the front of the chest. There is also a great pec stretch using a doorway which I included an a example of below. You can vary the arm positions high, middle, or low to get different angles fibers of the pec muscle.

Doorway Pectoralis Stretch for Upper, Middle, and Lower Fibers based on hand position – http://abbottcenter.com/bostonpaintherapy/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/doorwaystretch.jpg

- Prone I/Y/T for Middle Back Strengthening: Have the athlete lay face down on a spotting block with their shoulders just over the edge in the starting position. First have the athlete use no weight, and then progress to the 3-5 lb dumbbell range if they demonstrate proper form. The athlete will first raise the arms up to mimic the letter “Y” 10 – 12 times, then the letter “T” 10 – 12 times with the thumbs towards the ceiling the entire time. Keep the shoulder blades pinched together the whole time. This combination of exercises work the middle and lower parts of the trapezius, along with some of the rhomboid and other back muscles that help counter balance restricted anterior tightness. This will help to increase your athletes upper body posture, combat pectoralis tightness, and help balance the athlete’s shoulder joint. They don’t help to ensure proper mechanics of the shoulder blades moving around the middle back or thoracic spine, but they can help for your gymnasts to start to be more aware of their shoulder blade muscles. These are surprisingly rough when done properly

- Wall Angels: Have the athlete stand with their back against a flat wall. Bring the arms up to just below shoulder height with the elbows bent. Then, while keeping the back of the arms and middle black flat against the wall at all times, raise the arms overhead and hold for 1-2 seconds. This exercise is very good for postural awareness, but the gymnast must be sure they don’t pull their shoulders down and back as hard as possible, we want just a little bit of shoulder blades together. This exercise again doesn’t help with all the problems a gymnast may have related to their shoulder blades being stable and moving correctly, but it is a good postural exercise to start with. Start with no weight and progress to light dumbbells, performing 2 – 3 sets of 12. Again, surprisingly tough when done with correct form.

Horizontal Pull Up Variation: Horizontal Pull ups is a great exercise for developing pulling and back strength. The key difference in whether the exercise targets the lats or the middle back lies in the elbow position. If the elbows are pulled in by the rib cage during the exercise, it is primarily working the latissmus dorsi muscles. By having the athlete bring their elbows out to the side in a “T” position, it focuses more on the middle back muscle between the shoulder blades, which are what helps influence posture and combat rounded shoulders. Have the athlete use a block stacked to horizontal, then pull their chest to the bar with their elbows out the whole time. When done properly you will find your athletes may struggle. If horizontal is too difficult for your younger athletes, they can lower their feet using a smaller height block, and progress up. Remember, never sacrifice proper form. This is a great variation to add to strength circuits or strength programs.

With all of these concepts being considered, and remembering that lower back problems can arise from various factors, hopefully this is helpful to coaches/gymnasts to increase bridging related skill performance. As noted, many times the excessive extension can cause a problem that hip flexor and shoulder mobility can’t fix. Also, remember there can numerous contributing reasons that may be underlying if a gymnast is getting lower back pain. Many times it requires professional services and rest to properly resolve the issue. If this scenario is applicable and aids the athletes you work with, that’s fantastic.

This being said, you may be surprised of the results within your athletes or yourself if you investigate these two other areas that play a roll in the bridging position. I hope that this information is useful and it helps you/your athletes within the sport. As always feel free to use these ideas as you feel fit, and share the information with others. Best of luck,

Dave

References

- Mcneal, J.R., Sands W.A., Shultz B.B. Muscle activation characteristics of tumbling take-offs. Sports Biomechanics. September 2007; 6(3): 375 – 390

- Kruse D., Lemmen B. Spine Injuries In The Sport of Gymnastics. Current Sports Medicine Reports; 8(1): January/Febuary 2009.

- Sleeper, M.D., Kenyon L.K., Casey E. Measuring Fitness In Female Gymnasts: The Gymnastics Functional Measurement Tool. IJSPT; April 2012; 7(2): 124 – 138

- Page P., Frank C.C., Lardner R.. Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalances: The Janda Approach. Sheridan Books; 2010

- Cook G., et al. Movement – Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, Corrective Strategies. First Edition. On Target Publications, 2010.

- Oscar E. Corrective Exercise Solutions to Common Hip and Shoulder Dysfunction. Lotus Publishing: California; 2012

- Myers, TW. Anatomy Trains: Mysofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. Second Edition. 2009

- Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, Rodgers MM, Romani WA. Muscles: Testing And Function With Posture And Pain. 5th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2005:51-75.

- Page P., Frank CC., Lardner R.. Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalances: The Janda Approach. Sheridan Books; 2010

- Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Fifth Edit. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

- Brody LT, Hall CM. Therapeutic Exercise: Moving Toward Function. Third. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2011:197 – 204.

- Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskelatal System: Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. First. St. Louis: Mobsy Inc. 2002:103 – 111.

- Tkachev Reference: http://i2.wp.com/gymnasticscoaching.com/new/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Nabieva.jpg?resize=403%2C500

- Arch Hold Reference: http://gymnastics.isport.com/userfiles/Guide/image/Gymnastics/Gymnastics_Strength-Conditioning_01.jpg

- Front Walkover Reference: http://www.buzzle.com/images/sports/gymnastics/front-walkover.jpg

- Latissimus Dorsi Reference: http://www.exrx.net/Muscles/LatissimusDorsi.html

- Pectoralis Muscle Reference: http://ittcs.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/img_0363.jpg

- Pec Doorway Stretch Reference: http://abbottcenter.com/bostonpaintherapy/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/doorwaystretch.jpg

- Spondylolisthesis Reference Picture: http://www.pt-works.com/images/spondylolisthesis.jpg

- Spondylolysis Reference http://www.massgeneral.org/ortho/assets/images/pediatrics/spondylolysis-spine-drawing-l5s1.jpg

Great goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you are just too excellent.

I actually like what you’ve acquired here, really like what you’re saying and the waay in

which you say it. Yoou make it enjoyable and you stull care

for to keep iit sensible. I cann not wait to rdad far more from you.

This is really a great web site.

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really recognize what you’re speaking about!

Bookmarked. Kindly additionally talk over with my website

=). We could have a link exchange contract between us

You’ve gotten great information in this article.

I constantly spent my half an hour to read this weblog’s articles or reviews

every day along with a mug of coffee.

Thank you! I greatly appreciate the time you take to read, glad you enjoy the info