After a few weeks on break, I’m looking forward to getting back into posting some new stuff for readers. I just wanted to take a minute to thank everyone for their support and positive feedback regarding the site. I was blown away to find out this week that the site just tipped over 1,600 views across 34 countries in the last few months. Endless thanks go out to readers who have spread the word. I hope that through the blog I am able offer readers some possible insight and knowledge about injury prevention in gymnastics, while hopefully helping members of the sport in the process.

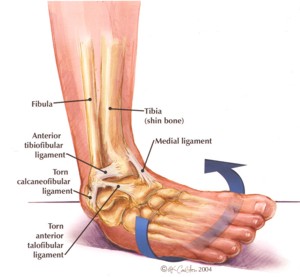

For this weeks post I wanted to write about a really common issue gymnasts deal with, which is instability/laxity of the ankle joints and athletes who suffer from chronic ankle sprains. Over the years, it seems like this is one of the most common issues that gymnasts and coaches ask me about. For a variety of reasons gymnasts typically develop very hypermobile ankle joints, along with large muscular imbalances, and associated laxity of the surrounding ankle joint structures. This can then possibly lead to a variety of repeated injuries one of which being reoccurring ankle sprains. Some really great research has been surfacing lately that discusses people may be at a higher risk of an ankle injury when these biomechanical factors are present.

When the ankle joint looses stability and it’s capability to tolerate high forces, problems may arise. The same authors noted above also outline that athletes participating in high level sports (like gymnastics) may be at higher risk of ankle sprains when they do not regularly practice preventative ankle balance/stability exercises. The most familiar scenario many readers can relate to is when a gymnast who is supposed to have amazing balance will land an incredible dismount, then roll their ankle walking off that mat and get injuries. Also, many athletes sometimes do more harm to their ankles by rolling them while walking around the gym or warming up.

Example of Position That May Cause an Inversion or “rolled ankle” sprain position

I’m not gonna lie, the picture above kind of gets me nervous knowing this gymnast may have been a very close to a possible sprain. Although inversion sprains are the most common, many other injuries can possibly develop from hypermobility and a lack of ankle stability such as stress fractures, bone bruising, anterior ankle impingement pain, and various arch related problems. By reading, I hope to give coaches and athletes some tips and techniques to combat excessively unusable ankles and possible prevent/reduce the occurrence of injuries.

Background

Going through every anatomical part of the foot and ankle would be very extensive and be about as fun as watching grass grow for readers. Instead, I wanted to focus more on some really cool information that has come out about an athlete’s ability to control the ankle joint, and link it to how you can directly use information to improve performance in yourself/ your athletes. I’ll bring up the anatomy concepts as needed. There is some fascinating information in the rehabilitation literature to neuromuscular control and why instability may occur, and they directly relate to gymnastics. I will use them to outline some contributing factors to instability, then move on to some exercises coaches and athlete’s can use to combat problems.

Neuromuscular Control

There are a few terms related to neuromuscular control that will help readers understand a lot about balance and anlke stability within gymnastics. Don’t be overwhelmed by them, I will provide the medical terms and their simple translation. These seem involved but they aren’t, just bear with me for a few paragraphs. If you take a few minutes to read through these concepts the information and your view on gymnastics might really change your thinking process, and your appreciation of gymnastics may sky rocket.

- Neuromuscular Control = I use this term from time to time in my posts. The simplistic definition for this refers to the interactions of muscles and nerves, and how they act to control the muscle/bone structures of the body.

- Sensory Input and Sensory Receptors = This refers to information your muscles and joints send back to your brain through nerves to gather information about the body. It happens in a matter split seconds. Different types of receptors send different information (muscle length, pain, temperature, pressure) through various nerve fibers. They have a lot of fun names like “Superficial Ruffini” and “fibrous capsule free nerve endings” which the majority of readers honestly don’t care too much about. The brain gathers information from these fancy named receptors and then processes it to understand what your body is doing. For example, when you catch your foot on a mat in the gym and are about to face plant, your body quickly sends information from your muscles and joints to your spinal cord/brain to let you know whats going on. This bombardment of feedback used for reflexes/quick processing is part of what allows gymnasts to detect quick movement and know whats happening in their body during skills.

- Motor Output and Muscular Activation = These terms deal with information your brain sends back to your muscles to move or activate muscles once it gets incoming information. The brain is constantly sending signals to all your muscles and joints about how to move and keep your body safe based on incoming signals from the body. For example, after your body sends information that you tripped over the mat, hopefully your reflexes and brain will tell your muscles to react and prevent you from that embarrassing face plant. Overtime through training, gymnasts often develop an ability to quickly react and activate muscles. This helps give them those cat like reflexes to stick landings and perform high level skills.

- Functional Joint Stabilization = Having an equal balance of muscles around a joint and proper neuromuscular control helps to keep it stable (assisting bones, ligaments, and joint capsules). The information coming in to the brain and going out its constantly buzzing like a busy highway, working to make sure joints are stable, safe, and working properly. Without this type of communication for functional joint stability, you would look more wobbly and unsteady (although arguably having smoother dance moves). Your body relies on the constant flow of information in and muscle activation out to function properly during movement. It is crucial for gymnasts to have good functional joint stability to tolerate all the forces gymnastics places on their bodies.

- Proprioception and Kinesthesia – These is probably the most important concept to understand. This terms simple refer to the brains ability to know where different body parts are in space. The more you train higher level balance and proprioception based exercises, the nervous system becomes more efficient at sending signals, receiving signals, and handling complex movements (like gymnastics).

I wanted to define those terms not to make people confused, but to show that they can be understood by coaches/gymnasts and used in their everyday lives.

In summary, based on the incoming information (sensory input), spinal reflexes are used or the brain interperts what each part of the body is doing (proprioception and kinesthesia) and sends outgoing information (motor output) to muscles and nerves to make sure joints are balanced (functional joint stability). See not so bad, and if you can wrap your head around that concept you will be in great shape to understanding why certain exercises really might help your gymnasts or you with wobbly ankles. When these neuromuscular components, and many other areas, are firing all cylinders gymnasts can optimize their gymnastics capabilities while also possibly preventing instability based ankle, knee, and other types of injuries. I will walk through some reasons why these thing matters, then give you some great exercises to help your athletes.

Contributing Factors

1) Gymnastics Creates High Forces at High Velocities = High Level Balance Needed

I feel like I say this in every post, but I think gymnasts and coaches kind of breeze over this amazing concept. Gymnastics requires an incredible amount of balance and functional joint stability to deal with high forces and fast movements. This alone requires that gymnasts must be able to quickly take in the sensory information, process it, then send back instructions on how to activate muscles during skills. Consequently, the athlete must have a really good proprioceptive/kinesthetic sense to meet the sports demand. Due to all the tumbling and jumping/landing (not to mention beam being an entire event based on ankle proprioception/stability) the ankles becomes one of the keystones to proper balance during gymnastics activities.

Example of High Force Through Ankles During Tumbling

If the athlete shows balance problems with basic skills and is very wobbly in their ankles, it may be important to add in exercises related to balance and proprioception at home, as a part of a event workout, or during practice. If this is ignored and the athlete is instructed to keep trying the skill, the gymnast may be at a much greater risk to suffer ankle injuries (like chronic ankle rollers) during complex skills. Not to mention the athlete may become quickly frustrated with their lack of progress for events like beam, and dealing with repetitive injuries. To meet the demands of the sport and promote optimal skill performance athletes need to practice a very high level of balance activities, which I will show some examples of below.

2) Toe Point/Plantar Flexion Bias, Hypermobility

Gymnasts commonly develop muscular imbalances of the ankle, and hypermobility of the joints while moving into these motions. This is often because,

- The sport of gymnastics is very “push the foot down and in” motion dominant because athletes are constantly using these muscles when they tumble, jump, and perform skills.

- Many times athletes have imbalances into a “down and in” position because the muscles that perform this motion are over developed.

- The “down and in” bias is often further amplified by a weakness into the “out and up” motions which is known as dorsiflexion and eversion.

- Gymnasts often develop and adapt an intrinsic learned motor pattern or behavior of automatically pointing the ankles down and in from gymnasts. Everyone who was a gymnast knows they automatically straghten their knee and point their toe at random points during their day or sitting on the floor. These motor patterns (including automatically pointing a toe to “down and in” become engrained in our athletes over time and seem to show up more and more in non gymnastics activities.

In this picture the yellow lines represent “0 degrees”/neutral, the blue line is an estimate to average plantar flexion in most people, and the red line represents an excessive plantar flexion angle during toe point.

Ankle Plantar Flexion

Along with excessive mobility into plantar flexion (toe point), gymnasts typically also have excessive amounts of inversion (ankle moving inward) over time. This is often due to

- Hypermobility/laxity of the ankle joint developing from repetitive impact based activities,

- The motion of “pushing off” during tumbling and gymnastics skills involving inversion

- Previous inversion based ankle sprains leading to overstretched structures on the outside of the foot, and

Below is an example of a gymnast who has excessive inversion mobility, and also has issues related to hyermobility/flat feet/chronic ankle sprains. The left ankle in this picture is what a more typical inversion range of motion would be (roughly 30-40 degrees) and the right is her actively moving into full inversion, which is almost double that of the normal range. I’m not gonna lie, it makes me cringe a little. Unfortunately, this is the case with many gymnasts.

Example of Hyper/Excessive Inversion (right) Compared To What A Typical Inversion Range Is (left)

A “rolled ankle” is known as an inversion sprain. This happens when the foot goes down (plantar flexion) and in (inversion) at the same time forcefully and pulls on the structures outside the ankle. Having crazy amounts of inversion and plantar flexion contributes big time to super mobile ankles the increased risks of rolling the ankle over and over with simple activities during the day (like stepping of a curb and not noticing your ankles heading in a bad direction before it’s too late).

As you might be realizing, if the foot is constantly in that “down and in” position, with hypermobility and an imbalance of the ankle muscles present, this may be why a gymnast sprains their ankles over and over. The imbalance create a scenario where the foot more regularly assumes the “down and in” position. This may possibly lead to catching the foot and rolling it during walking, tumbling, and landing. By staying ahead of these imbalances and working on some proprioception/functional joint stability, it may help to reduce the instability in the ankle while possible reducing injury rates/increasing skill performance.

3) Psychological and Neuromuscular Fatigue

Psychological stressors and fatigue levels are often over looked as a huge factor into why athlete’s biomechanics, neuromuscular control, and ability to prevent injury fall apart when practicing gymnastics. When an athlete is under high pressure situations (new skills, routines, etc) and when they are fatigued (high number of reps, end of routines, end of practice, beginning of competition season) their ability to perform is greatly effected. Along with this, there is some really cool research that that supports this and suggests that under these fatigued conditions the body looses some of its ability to received and processes information (sensory input/proprioception). They explain that receptors loose some of their ability to send signals from the joint and muscles that are responsible for sensing pressure, muscle length, and joint tension. This in turn decreases an athlete’s ability to know where their joints are in space (proprioception and kinesthesia). This may then lead to a decreased ability to correct for a variety dangerous forces that may cause a variety of injuries (many at the ankle joint) and predispose someone to an injury.

It is crucial for athletes and gymnasts to realize the impact that psychological and fatigue within their gymnastics training, specifically for the ankle. The ankle is one of the most functionally important joints in gymnastics for proper balance and high level skill performance. Members of the sport must be proactive these issues. One aspect is related to the volume and demand of training. Proper transition of landing surfaces and highly complex new skills may not be best for fatigued situations. Along with this, it may be of benefit for coaches to implement proprioceptive and balance exercises that do not have as much risk involved (like the exercises below) at the end of practices to simulate these circumstances. In some scenarios, exchanging high risk skills under fatigue like new skills/dismounts for high level proprioceptive exercises that have less consequences may be useful. This may help to possibly reduce lower extremity and ankle injuries while also increase the athlete’s ability during their training.

4) Recurrent Ankle Injuries and Repetitive Damage

As I have hinted at in other posts and this one, faulty biomechanics without proper care for the body may lead to repetitive damage of structures. The ankle is one of the most common sites for this to happen, due to the demand placed on it in the sport. Reoccurring ankle damage and injury to the ankle joint has a link to instability, that may lead to ankle (and other joint) injury. There is literature and research to support that when injury and tissue damage happens over and over, it effects the communication between the body and brain (sensory input) and response time of the brain to the muscles (motor output). The theories suggest that the continued injury causes damage to the receptors and nerves of the ankle, possibly contributing to further more serious injuries like ligament and bone damage.

This directly relates to the sport of gymnastics and why many injuries may build up for athletes over time. If an athlete is pushed constantly to train and perform high demand skills, it may then lead to progressive decrease in proprioception and possibly a big time injury some day. There is research that suggest that people with recurrent ankle instability alter their overall body mechanics as compensation and may result in related injuries over time.

As you may see plantar flexion and inversion muscular imbalances, a decreased ability to sense ankle motion and correct a sprain in progress, hypermobility, and fatigue can all play a roll in chronic ankle injuries for athletes. Gymnasts and coaches must be ahead of the curve when it comes to ankle instability problems, so they can continue to function at a high level in the sport, hopefully prevent injury, and progress to complex skill levels.

How to Help with Strengthening, Functional Stability, Balance, and Proprioceptive Exercises

With this information as some support to why training these exercises is so important, I want to offer some strengthening and higher level balance exercises athletes and coaches can utilize. These can be done as a circuit with other pre-hab activities, added in as active rest stations for events/conditioning, or done at home if time is limited. Be a stickler for good form and biomechanics, while making sure the athlete’s safety is most important.

Working on Ankle Muscular Imbalances

The most basic way an athlete can work on the muscular imbalances is to release tension in the muscles that are over developed (plantar flexors/”down” and inversion /”in”), and work on strengthening the muscles that may be long and weakened (dorsiflexion/ “up” and eversion/ “out”). Here are some myofascial release techniques for muscles (gastrocnemius, soleus, posterior tibialis) that are usually overdeveloped in athletes who have an inversion and plantar flexion imbalance. Rolling the toes inwards and working along side the calf muscles will also hit the posterior tibialis, which runs it’s course along this path. Here is a anatomy picture to use as a references.

Myofascial Release Techniques Using Foam Rollers/PVC Pipes/Lacrosse Balls/Tennis Balls

Myofascial Release For Calves

Elevated Myofascial Release for Hamstrings Using Racquetball

Gastrocnemius and Soleus Stretches Using Beam Base

Gastrocnemius Stretch Using Beam Base

Soleus Stretch Using Beam Base

Strengthening Eversion and Dorsiflexion Muscles

Along with this, athlete’s can also do some exercises to strengthen the opposing muscles that pull the ankle up (dorsiflexion) and ( fibularis longus/brevis). For eversion “out” have the athlete wrap a band around the outside of the foot with the tension going towards the inside of the foot, and pull the toes outward. Do a few sets of 15 with the proper resistance.

Toe strengthen the muscles on the front of the ankle that pull the toes “up” into dorsiflexion, an athlete can use a springboard. The gymnast will stand with their toes hanging off the edge of a springboard. They will then pull their toes up to their head on one foot and hold, then switch to the other. Do a few sets of 15 correctly and you might be surprised how fast you start to feel it.

Single Leg Toe Raise on Springboard Front (Harder Due To Depth) – End

Single Leg Toe Raise on Springboard Front (Harder Due To Depth) – Start

Proprioceptive and Kinesthetic Exercises

The exercises require an athlete to close their eyes, stand on an unstable surface, or perform dynamic movement stress the sensory and proprioception more, which is what we want. This is why blind landings during skills (decreased visual input), and landing on a stack of mats (unstable surface) can be challenging. Coaches and athletes want to use these to their advantage in an attempt to simulate complex balance situations when doing skills. These exercises are a combination of research and literature based tests, combined with gymnastics based activities I have picked up over the years. I apologize in advance for the quality on some pictures being a little low, I had to take them off my phone’s video and it was a little tricky. Also keep in mind the pictures of the athletes are perfect, they all show some off mechanics they are still working to improve upon.

Single Leg Eyes Closed Balancing on Floor/Foam

In terms of exercises that will be hard for gymnasts, this is probably one of the bottom tiers to start at. The athlete will stand on a piece of cut foam (or a foam cube/mat) for 30 seconds with their eyes closed. The easiest version of this drill would be standing on a flat surface, with your eyes open. Then you can make it more difficult by changing some of the conditions. Standing on an uneven surface makes it hard for your ankle to detect the movements, and it has to work a lot harder to stay balanced. Closing your eyes further challenges the gymnast because it eliminates visual input that someone would normally use to keep their orientation to vertical, and it stresses the sensory motor system/inner ear a lot more. By standing on one piece of foam close to another person, it makes it even more difficult because you have to adjust to your own body movements as well as the other person wobbling. Eyes closed, on foam, with another person close is pretty tough to do. Start with whatever version fits your athletes best, then build in more of the advanced versions and higher level exercises below to add to the challenge.

Partner Single Leg Stance Balance Drills with Eyes Closed

Dynamic Star Excursion Exercise

This is a really good place for coaches and athlete’s to start to test their ability to control their body over one leg. Along with this it works on multiple factors like strength, balance, flexibility, and proprioception.

- Have the athlete stand with a “triangle” of cones around them, one in front and one out and behind on each side. They should be slightly outside their leg reach to make it tough.The athlete will stand in one spot on a line on one leg in the middle of the triangle. Make sure to instruct the athlete to keep the torso and core tight, and only move the hip/leg to reach for the cones. Many athletes will instinctively move the trunk and turn their body to make up for lack of balance.

Star Excursion Balance Drill Start

- Without moving the base leg and while keeping the trunk still, the athlete will move the leg that is off the ground to tap each cone in a circular pattern. The athlete will tap the front cone, the cone out to the side, and the cone behind and to the other side. This exercise will help to both see a athlete’s balance capability but also work on the problems.

Star Excursion Balance Drill Front – Step 1

Star Excursion Balance Drill Side – Step 2

Star Excursion Balance Drill Inward – Step 3

Here is an example of a series of these stations set up during a pre-hab circuit. These can also be added during events as an active rest, or can be given to athletes to work on it time is limited.

Star Excursion Balance Drill Circuit

Full Single Leg Squat To Block With Eyes Closed

This type of movement bridges the gap to static balance and dynamic movement that the athlete will need to utilize with skills. The athlete will stand in front of a trapezoid or medium sized block. Then with eyes closed the athlete will slowly lower down until they are sitting on the block, pause, and rise back up to a full stand. Dowels can be used to hold on over the shoulders for promote proper upright trunk alignment. Coaches and other athletes must watch for proper form, good alignment, and smooth control to ensure joint safety. Perform a few sets of 8 on each leg to help encourage muscular fatigue and prolonged control. Intuitively you may ask why the athlete is in front of a mirror if their eyes are closed. The reason is that because most often times athletes will have some compensation during the squat movement, and fall out of good alignment.

It is good to have the athlete open their eyes between reps and reset to a proper mechanics, rather than do 1 good rep then keep their eyes closed and crank through 4 reps with terrible biomechanics. Also, you have to make sure the height of the block is not too challenging, adjust the block to fit each athletes capabilities and personal height (don’t use the same block for a peanut level 6 with worse balance, and a tall level 10 with more developed balance).

Single Leg Squat Proproceptive Exercise with Eyes Closed – Start

Single Leg Squat Proproceptive Exercise with Eyes Closed – Start

Single Leg Squat (Eyes Closed) – Start

Single Leg Squat (Eyes Closed) – Middle

Single Leg Squat (Eyes Closed) – End

Forward and Lateral Hopping with 1/4 Turn Using Panel Mat (Eyes Open)

This exercise should be done with the athletes eyes open for safety reasons, and helps to further stress proper biomechanics. The athlete will stand on one leg in front or on the side of a panel mat. Then, the athlete jumps and does a 1/4 turn up to the mat, holding the landing position in a single leg squat for a few seconds. The athlete hops back down turning 1/4 back, then goes in the other direction. This exercise is good to combine hopping, landing, and stabilizing the knee during movement. Again, a few sets of 8 -10 on each leg will allow fatigue to set in and further challenge the gymnast.

1/4 Jump To Single Leg Hold – Start

1/4 Jump To Single Leg Hold – Ascending Flight

1/4 Jump To Single Leg Hold – Hold Position

1/4 Jump To Single Leg Hold – Descend Position

1/4 Jump To Single Leg Hold – End

Quick Taps on Panel To Single Leg Hold (Eyes Open)

This exercise helps to further challenge a gymnast’s ability to accept both make quick movements with functional stability, then also control forces to become stationary (simulating tumbling and landing/dismounts). The athlete will stand in front of a medium sized block or trapezoid starting at one end. The athlete will quickly alternate tapping each foot while traveling down the mat, and after the last tap the athlete will assume a single leg hold. Then the athlete will travel back down the block in the other direction, stopping on the other foot at the end of the mat. Here are some pictures to help explain the process.

Quick Taps on Panel to Single Leg Hold – Start

Quick Taps on Panel to Single Leg Hold – Middle 1

Quick Taps on Panel to Single Leg Hold – Middle 2

Quick Taps on Panel to Single Leg Hold – End in Hold Position

Lunge Jump with 1/4 Turn to Panel Mat With Eyes Closed Single Leg Squat

This movement is pretty challenging for athletes to perform correctly. The athlete will stand besides to panel mats in a lunge position to start. They will jump off of one leg, perform the same 1/4 up to the panel, and hold the single leg squat. However this time, when the athlete fully lands and is in control, they close their eyes and holds a single leg stance for 3 seconds. The athlete then opens their eyes, and returns to the starting position, and repeats. Holding a single leg stance on the panel mat with the eyes closed really challenges the athlete because the mat is unstable and they don’t have their eyes to help. Make sure safety is the most important, and the athlete only closes their eyes once they are fully stable on the panel mat (not while jumping). Also, stress proper body mechanics and cue the athlete to fix problems as they go.

Lunge Hop 1/4 To Panel – Start

Lunge Hop 1/4 To Panel – Flight

Lunge Hop 1/4 To Panel – End Hold with Eyes Closed

Concluding Thoughts

I know that there is a lot of information within this post, but if you take just the basic ideas and apply them in your gyms it may really make a big difference for yourself or your athletes who have really unstable ankles. I personally believe that if athlete’s want to reach high levels of performance they need to be attentive to concepts like this. It will allow them to be very skilled at complex balance activities gymnastics requires like on beam, but also possibly reduce their risk of getting an ankle injury with repetitive gymnastics training. Integrating some of these exercises may help to increase an athletes capabilities while trying to keep them safe and involved in the sport as much as possible. They should be challenging for the gymnast. We want to make it hard for their systems so they can adapt and train their neuromuscular control.

Remember that this post by no means encompasses all the information on the topic, or that these exercises are the “gold standard” of dynamic balance. There are tons of ways to approach something like this and I am learning more myself every day. For now, I hope that the information and exercises may find it’s way into your daily gymnastics adventures. Best of luck,

Dave

References:

- Clanton, TO. Return to Play in Athletes Following Ankle Injuries. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. October 2012; 4 (6): 471 – 474

- Martin RL, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Ankle Stability and Movement Coordination Impairments: Ankle Ligament Sprains. JOSPT. September 2013; 43(9) A2 – A40

- Wertz, et al. Achilles Tendon Rupture: Risk Assessment for Aerial and Ground Athletes. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Sept/Oct 2013; 5 (5): 407 – 416

- Bradshaw E.J., Hume P.A. Biomechanical approaches to identify and quantify injury mechanisms and risk factors in women’s artistic gymnastics. Sports Biomechanics. 2012; 11(3) 324 – 341

- de Vries JS., Krips R., Blankevoort L., van Dijk CN. Interventions For Treating Chronic Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review. The Cochrane Library; 2011 (8)

- Cook G., et al. Movement – Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, Corrective Strategies. First Edition. On Target Publications, 2010.

- Oscar E. Corrective Exercise Solutions to Common Hip and Shoulder Dysfunction. Lotus Publishing: California; 2012

- Myers, TW. Anatomy Trains: Mysofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. Second Edition. 2009

- Page P., Frank CC., Lardner R.. Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalances: The Janda Approach. Sheridan Books; 2010

- Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskelatal System: Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. First Edition. St. Louis: Mobsy Inc. 2002:103 – 111.

- Umphred DA.Neurological Rehabilitation. Fifth Edition. Philideplphia: Mosby, Inc; 2007

- Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

- Brody LT, Hall CM. Therapeutic Exercise: Moving Toward Function. Third Edition. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2011:197 – 204.